Scaling Community Nurseries Restoration through Leadership of Traditional Lafkenche Custodians in Budi

By Alison Guzman, Ignacio Krell, and Fernando Quilaqueo

In this brief article our team presents the efforts devoted in the first months of 2020 ( before quarantine!) to envision, plan and implement restoration actions and environmental stewardship by the Lafkenche communities in Ayllarewe Budi and their allies, a process driven by Fernando Quilaqueo Calfuqueo, who has collaborated with MAPLE Chile since 2016.

Lafkenche Environmental Custody: connecting the fragmented, from the micro to the territorial

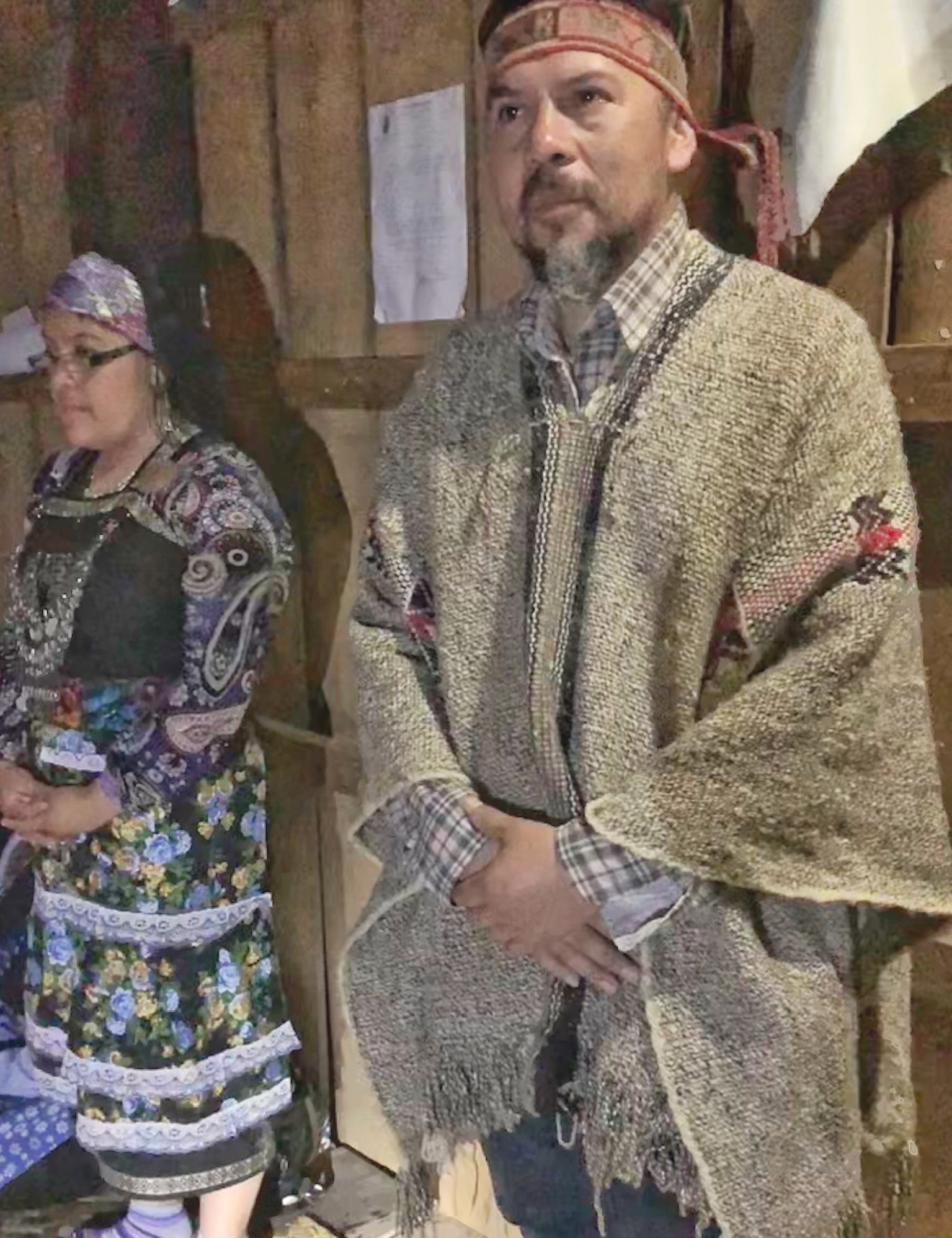

Born and raised in the Lof Mapuche of Llaguepulli, Fernando is an experienced agricultural technician and agro-ecologist, having collaborated in various productive and cultural projects with the Mapuche-Pehuenche communities in the Lonquimay mountains and the Lafkenche communities of Saavedra and Teodoro Schmidt. After five years living away from his community - just as many young people from the Lof Llaguepulli- he arrived in Santiago in search of better employment. In 2016 he was presented with an opportunity to return to the Lof to join the team as Field Coordinator for our program on strengthening food and local livelihoods through agroecology and agroforestry, his areas of specialty. Since then, living their lives at the Lof, Fernando and his wife, Elizabeth, have also collaborated with a community tourism venture focused on environmental interpretation and traditional Mapuche herbal medicine. In addition, Elizabeth is a gifted weaver and active participant in the ArtistriSud organization (based in Montreal, Canada). Together they have a son.

In these 4 years, the land he inherited from his ancestors in Llaguepulli, has become a model space for a contextualized agroecological transition, both for visitors, and for the members of the community, as well for our team. Fernando, during our last visit to his garden this last summer - a half hectare filled with native, healthy foods and seeds nested by native vegetation, medicinal plants, and only a few meters from it, a natural spring or menoko in mapudungún- he spoke to us about some of the challenges and achievements along this regenerative transformation of his family space:

"The issue with eucalyptus trees is that, although they may be useful (as firewood), they guzzle too much water. For 20 or 25 years what you see here was plagued by eucalyptus. There are still some left, but I've been slowly eliminating them. The other threat was overgrazing, and since the vegetation cover was minimal, much erosion occurred. Now tmy entire garden is surrounded by many diverse native trees: maki, hualles, native hazelnut (Gnefu) and Koiwe, to name a few. In addition, with the rainwater harvesting system l have installed on the roof of the house, which is connected to an efficient irrigation hose, I water my garden and help plants grow even more. Here, for example, we have squash, corn and beans, the "Tres Madres", a polyculture technique by our brothers from Central America. Also here in the garden I have three types of mapuche quinoa, or kinwa. In the menoko(water spring), which is here next to my garden, I have carried out a restoration work that has been going on for 5 years, and where notable progress is already being seen. I grew up in this community. As a child, when there was not yet a tap water system, we would fetch water from this menoko. Back then, as children, we came to this menoko from the houses, which were quite far removed, to fetch water, and here there was one very nice water source, precious really. Since I came to live here again, I have been working to gradually recover this menoko. It was all covered with eucalyptus, which I have been chopping out little by little. At some point they had burned all the native vegetation, so now I am recovering it, planting small native trees, ferns, and Chilean rhubarb. It is a long term job. That’s why the progress we have made is step by step, but I have confidence that I will have a nice menoko again: right now it is a bit dry, because it is summer time. But in winter, it will be flowing again.”

This did not happen overnight: Even in 2016 , Fernando shared with us his vision to restore the health of his territory, and especially the significant menoko, through a video clip you can see by clicking here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=YLTdSpgigL0&feature=emb_logo

What is more important, the vision of Fernando for restoring his space and economy is not only for personal reasons, but is also about the collective and of the territory; about the Mapuche-Lafkenche worldview and its reconstruction. Since 2016, as part of a team commissioned by the Longko (chief) Jorge Calfuqueo, Fernando has led different lines of work related to the agro-ecological production, regenerative agroforestry, community finances through the Mutual Support Group, and biocultural restoration through the creation of the Community Nurseries and Restoration Network. He has a lot on his plate and is the type of leader his community needs, leading youth and families wanting to create environmental resilience.

Fernando Quilaqueo

The emergence of a new territorial management tool in the Ayllarewe Budi

Since the beginning of the collaborative agroecological transition program in Llaguepulli in 2016, the horizon of our team has been the gradual scaling-up the learning process and regenerative efforts, through dialogue and replication tools useful in the cultural context, from the family to the community, and from there to the territorial: the ancestral territory Ayllarewe Budi is made up of more than 100 different communities. After several instances of inter-community dialogue, learning, and community work, three communities or Lof of the south of the Budi formed a network of community tree nurseries, which was formalized by the end of that year as the Environmental Association Budi Anumka, a non-profit organization made up entirely of Lafkenche environmental leaders. According to its statutes, the BUDI ANUMKA, has the purpose “to promote the restoration of the itrofillmonguén or biodiversity through coordinated action by indigenous communities, and can carry out their activities in the following areas of action:

Environmental training and education.

Sustainable, transparent and participatory management of community nurseries of native plants, as well as other initiatives that contribute to the restoration of biodiversity.

Promotion of the participation of indigenous communities in the restoration of biodiversity, through dialogues and activities of mutual support, and respecting their differences and autonomy.

Formation of support, collaboration and exchange networks that enhance the capacities of Mapuche communities and organizations to restore the biodiversity of their territories.”

In March 2020, MAPLE and BUDI ANUMKA were invited to present an expression of interest to the Global Environmental Facility ( GEF), through one of GEF’s partners, Conservation International . According to its website, https://www.inclusiveconservationinitiative.org/ , the GEF's Inclusive Conservation Initiative (ICI) aims to give prominence to indigenous peoples and local communities in their continued efforts to safeguard their natural ecosystems of the Earth, recognizing the historical roles they have played in the conservation of nature.

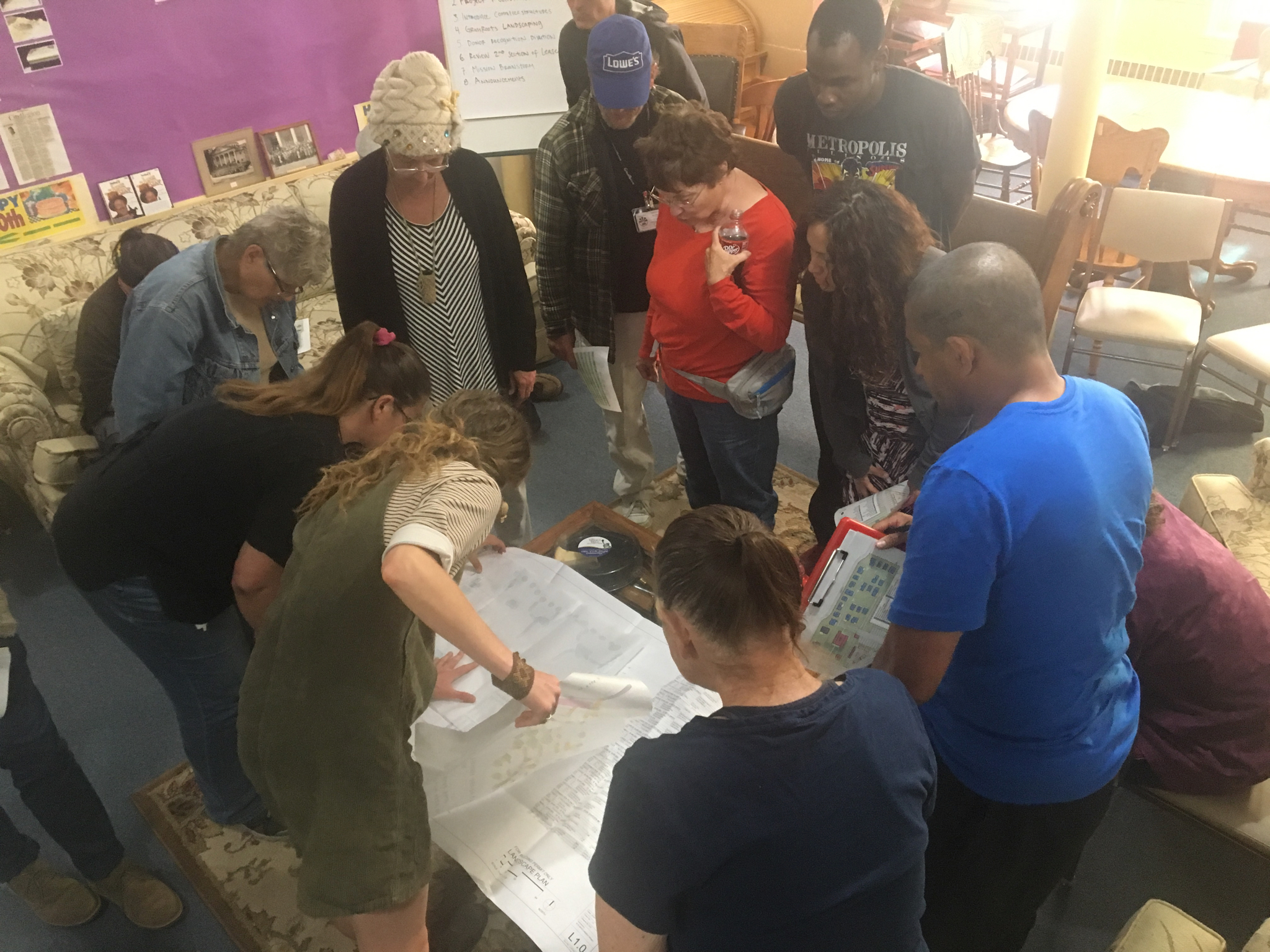

For our team, and Fernando now as leader of BUDI ANUMKA, the most immediate challenge, and perhaps the biggest so far, after receiving the invitation to apply to the Inclusive Conservation Initiative, was to convene a strong coalition to lead the territorial restoration and custodianship that should involve an increasing number of communities and their traditional custodians of the Ayllarewe Budi, in order to guarantee their full participation and incidence in the project from the very beginning.

As we explained in the proposal prepared for this Initiative by our team during April and May 2020, in dialogue with the custodians and traditional authorities of the Budi territory,

For the Mapuche being, all the elements of nature are vital. The balance of each of these elements on earth is intrinsically linked to health and overall development of the Mapuche in the earthly and spiritual aspect. The survival of future generations depends on continuing to recreate and safeguard livelihoods coexisting with our natural environment: it is what we conceive of as Good-living or Kvmemongueleal.

The long-term goals of our communities include restoring our space, culture, and identity as Lafkenche People. In the long term, we will create a fair economy linked to the conservation of wetlands and their goods and services, where the fruit of our work not only benefits our own families, but also the community in general with all its surroundings.

The proposed project is territorial in nature and therefore these objectives will be addressed in a gradual and phased manner. At first instance, the restoration work will be prioritized in the axes of the project communities, to give way, through dialogue and mutual learning, to the next communities that wish to incorporate.

The protection of the value of biodiversity and cultural heritage of the territory and its wetlands will be prioritized (which will be achieved) with documentation of a Framework of Traditional Custodianship jointly with the creation and empowerment of a Traditional Custodianship Council during the project (which) will promote indigenous environmental governance and the valuation of inclusive conservation by all the actors in the territory and its inclusion in policies and regulations at the local, national and international levels.

In the annexes, we partially present the minutes prepared as a record of the dialogues conducted over a month of consultations with an initial group of 10 Lafkenche custodians of the vast territory of the Ayllarewe Budi, who would integrate some of the following Rewe (centers ceremonial / territories) that make up the larger territory. They were invited to join this effort to reestablish and document the links between custodians of the traditional territory.

In the coming months we hope to hear about the development and support achieved by this initiative, which emerged from within the families, spaces, memory and Lafkenche custodianship norms of the ancestral territory Ayllarewe Budi, while we continue to walk with our allies towards general objectives and consensual.

ANNEX 1: REWE OF THE AYLLAREWE BUDI

In the Municipality of Teodoro Schmidt

In the Municipality of Saavedra

1.-Malalhue

2.-Yenehue

3.-Vest

4.-Puyehue

1.- Llangui

2.-Kechukawiñ

3.-Huapi Comuwe

4.-Weicha

5.-Panku

6.-Rugupulli

ANNEX 2 : MEETINGS MINUTES OF SOCIALIZATION OF THE INITIAL PROPOSAL OF THE CUSTODIA LAFQUENCHE PROJECT OF THE BUDI TERRITORY AND ITS WETLANDS

April 02, 2020, Llaguepulli Lof

(During our first) meeting with the longko of the Llaguepulli Community :

Firstly, a document was presented with preliminary proposals for the Lafquenche Environmental Governance Project at the Lake Budi / Aylla Rewe Budi Lewfu Level, in order to socialize and share their point of view as a traditional authority of a Lof where they are making significant efforts in the restoration and awareness of caring for the natural environment (itrofillmonguen). This document was prepared by Maple Microdesarrollo and the Budi Anvmka Environmental Association. Don Jorge expressed a high degree of interest in this proposal, noting that it would be appropriate to work on a project of this magnitude in the territory at this time for the protection of our environmental assets. He also agrees that the Budi Anvmka Association is in charge of presenting the Expression of Interest with the technical support of Maple Microdevelopment, but he also indicated his concern about the way, we would approach this territorial project and involve all actors, especially the traditional authorities, given the complex current organizational reality of each of them (Commune of Teodoro Schmidt and Saavedra) and the Covid-19 pandemic. And finally he offered his support so that this initiative has a happy ending.

April 21, 2020

This meeting was held at the house of the Guenpiñ (ceremonial orator) of the Malalhue Chanco community, with the participation of the president, treasurer and secretary of the Budi Anvmk Environmental Association, and that of peñi Juan from Malalhue-Chanko.

The main objective of this meeting was to share the initial proposal of the working document that is being prepared by the NGO Maple Chile with the consent of Budi Anvmka, plus the Longko (Main Traditional Authority) of Lof Llaguepulli to participate in the Environmental Fund contest World (GEF) where the deadline to present the expression of interest is May 30, 2020.

At the meeting the working document was shared, in detail, the design of the project; there was consensus that the Association Budi Anvmka and traditional authorities were the main players, because that is how autonomy is guaranteed both the project and future decisions that a project of this size would entail; in addition these personalities would generate a bridge to incorporate more relevant actors to this project.

The main objective of the proposal is to strengthen and enhance environmental governance Mapuche for restoration and conservation of Lake Budi and its wetlands, reflecting the social and cultural importance of biodiversity (ixofillmonguen ) of these territorial spaces.

As for the main Partners of the project, it was proposed to incorporate a strategic means of communication, in this case the Community Radio Werken Kvrvf - they would be a good alternative for the dissemination and socialization of the project in the territory.

With respect to the four annual stages, emphasis was placed on the gradualness and accompaniment in each of the specific objectives, to guarantee the success of this project, due to the ambition of the project, as stated in this working document, the methodological incorporation of research, documentation and socialization through the Gvlam (advice) and Nvtram (conversation) in the activities.

In addition, it was discussed how important it is to equate or revalidate the Aillarewe territorial organization system to manage and order our natural resources autonomously and standardize it according to the rights of internationally recognized indigenous peoples, but which is not respected here.

As a strategy, the genpiñ or traditional authorities of our rewe (yenehue) will first be approached, through their homes, to socialize and request the support of our initiative, later the same will be done with authorities from other rewes, according to the Actors Maps - delegating Juan and Fernando for this function - these activities will be of vital importance for the formulation of the expression of interest.

STEPS TO FOLLOW: Preparation of the Map of Actors and the scheduling of the field visits, with the help of the peñi Juan Rain, Fernando Quilaqueo and methodological collaboration of Alison Guzmán and Ignacio Krell.

April 27, 2020

A second meeting was carried out with peñi Juan Nguenpiñ of the community Malalhue Chanko in his home. The objective of this meeting was to coordinate and configure the Map of Actors that would constitute in the first meeting approach with leaders, lonkos, machis, machil, etc.- in order to fully address the conservation project Environmental Custodians whose expression of interest will be presented jointly with the Budi Anvmka Environmental Association.

In addition, also mention that with Juan, we have been mandated by Budi Anvmka to carry out the work of socializing and seeking support from relevant actors in the territory of the Buddi and coordination on the ground for the presentation of this project.

For the creation of the first list of Relevant Actors in the territory, we decided to incorporate some basic criteria: 1) Traditional or functional leaders , machis, machil , artists and / or artisans with a clear perspective related to Mapuche thought (mapuche rakizuam). Here we will mainly incorporate young actors available to work in line with this project, who are benchmarks in their territories with a gender focus and with the ability to convene. 2) It is sought to generate a high representativeness of the territory, through the traditional form of the Mapuche organization Lafkenche Ayllarewe , as a strategy, in the first round of visits, the authorities of the Budi basin will be contacted who will then refer or suggest to us other relevant actors.

A list of more than 30 relevant actors was drawn up in the first instance with the possibility of incorporating more people, as appropriate, but in the first round we will only visit approximately 10.

May 05, 2020

This (third) meeting was held at the home of the Juan, with the aim of coordinating visits to the leaders or relevant actors who support our expression of interest "Indigenous Custodians of the Budi Lake Wetland" to be presented to the GEF.

We analyzed the final document of the proposal where it is suggested to incorporate the Aillarewe Budi concept, as a way of appropriating this organizational system in the project, but in general the background and the letter of support would be appropriate.

In a strategic way, we will visit in the first instance the closest leaders who in some way know the process of the environmental restoration work that is taking place in our communities in Budi Anumka. From our point of view, it would also be interesting to make at least two to three audiovisual records to support this expression of interest.

Thursday May 07, 2020

Oscar Carrillo and Fernando Quilaqueo part of directors of BUDI ANUMKA held meetings today with three authorities of the Mapuche Llaguepulli Community in order to address and seek support for the presentation of the expression of interest in the Custodios Ambientales del Budi project.

In the first instance, we met with Longko del Lof Llaguepulli at his house, who, by reviewing the summary document of the proposal, expressed his agreement with respect to all the points established in said document, while maintaining that he would support the project in the measure that was necessary with unanimous support for Oscar and Fernando, for all the work carried out in the Community's environmental restoration program and also the holistic approach of this pioneering restoration initiative so far as an initiative. The longko agreed so that together we could make an audiovisual note of support to be attached with the expression of interest, this was scheduled for Friday, May 15, 11 am in the community tree nursery Kom pu Lof.

The next meeting we held with a family, also very prominent, of the lof with the Kimche and Lawentuchefe Fresia and her granddaughter Ana, who is currently entering a process of Machil- both were available to participate and support this expression of interest , and in their account, particularly Papay Fresia, she introduced us to the history and landscape and cultural transformations suffered and our territory from no more than half a century. Both agreed to sign a letter of support for the expression of interest.

May 08, 2020

Today being the 5 pm Oscar Carrillo and Fernando Quilaqueo We made a visit to the nguenpiñ of the lof Wente, the meeting was held at the home of this, with the aim of socializing the Custodians project Lafqueche and will be made known or by the Budi anumka Environmental Association to the World Environment Fund in the course of this month.

He belongs to a generation of renewal in the role of traditional Mapuche authorities, who are leading in the territory, an important renewal work, in this case, inherited by his father. The work of Budi Anumka in a territorial context was explained to him, as well as the character of this project by Custodios AillaRewe Budi, he mentioned to us in a testimonial way the philosophy of life that they, as a family, have been developing since he has memory clinging to the mapuche moguen as their fundamental source as conservators of their native forest and menoko.

Along with wishing us much success in our expression of interest, he expressed his full support, in addition to committing to socialize the idea with his closest group in his community.

The signing of a letter of support for this project was finalized, leaving a copy of the summary and letter of support in his possession.

ANNEX 3: EXPECTED RESULTS 2021-2025

1. Indigenous Biodiversity Conservation of the AYLLAREWE: Communities of the Budi incorporated directly to a restoration of the wetland Budi, producing global benefits and biocultural territory resilient to climate change. The Budi Lake Coastal Wetland (56.2 km2), with at least 120 species of birds, some of them in danger of extinction, and whose brackish ecosystems represent the bio- cultural heart of the coastal territory of La Araucanía (Northern Patagonia, Chile), was declared a Priority Conservation Site and a candidate for the Ramsar List in 2002.

2. Capacity, Knowledge and Research: Safeguarding the value of the biodiversity and cultural heritage of the territory and its wetlands with the documentation of a Traditional Custodianship Framework, and the identification of biocultural indicators and community priorities such as conservation, restoration and use sustainable water, medicinal plants, small-scale fisheries and fish farming, and family agroecology, with full participation of traditional custodians. The synergy between a) the conservation of the coastal wetlands of Northern Patagonia and its global benefits for mitigation and adaptation to climate change will be strengthened, b) the growing voice and environmental governance of our local communities, exercising their traditional role of Custodians.

3. Stakeholder development: The creation and empowerment of a Council of Traditional Custodians during the project will promote indigenous environmental governance and the valuation of inclusive conservation by all the actors in the territory and its inclusion in policies and regulations at the level local, national and international.

4. Gender equality, community economies and retention of rural youth Lafkenche: Greater inclusiveness through the creation of the Lafkenche Women's Steering Committee to guarantee women's participation in community governance, generating new capacities for biodiversity management and new sustainable livelihood strategies based on the sustainable management of wetland services, the production of native plants and foods, and the addition of value to medicinal resources, foodstuffs and fibers of forests and wetlands .

5. Innovative and influential models: Consolidation of a sustainable model for the indigenous conservation of Lake Budi wetlands and its dissemination to other actors at local and national level to promote favorable conditions for its scaling, replication and projection over time.